Archivieren als radikale Handlung

Die Referentin #41

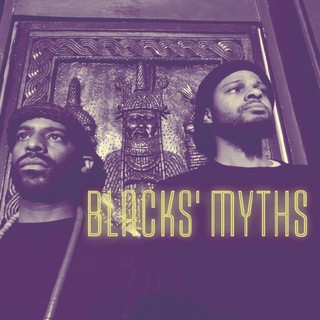

Das Festival Cinéma Africain! findet heuer von 5.–8. November in Linz statt und bringt Filme aus Afrika und der afrikanischen Diaspora nach Linz. Zur diesjährigen Ausgabe des Festivals wird außerdem eine Publikation erscheinen, die auf das weitverzweigte panafrikanische Filmschaffen verweist. In dieser Referentin finden sich Texte aus der Publikation.

June Givanni. Foto Lewis Patrick

Im Oktober 2024 fand in Linz die erste Ausgabe des Festivals Cinéma Africain! statt. Um das afrikanische und diasporische Kino auch weiterführend zu thematisieren, wurde danach eine Publikation initiert, die die Rolle des afrikanischen Kinos hinsichtlich seiner Narrative, der Bewahrung des kulturellen Gedächtnisses und der Infragestellung vorherrschender Perspektiven beleuchtet. Die Herausgeberinnen Sandra Krampelhuber und Nadia Denton nahmen sich eine Textsammlung zum Ziel, die über akademische Kreise hinausgeht, eurozentrische Sichtweisen hinterfragt und die vielfältigen Traditionen des afrikanischen Geschichtenerzählens würdigen sollte. Im Rahmen des diesjährigen Festivals „Cinéma Africain!“ wird nun die Publikation „Cinéma Africain – Archiving, Resistance and Freedom“ vorgestellt. In dieser Referentin sind vorneweg zwei Texte aus der Publikation zu lesen, die sich dem Reichtum afrikanischer und diasporischer Erzählkunst im Film widmen.

Im folgenden Beitrag interviewt die britische Kuratorin Nadia Denton die Filmschaffende und Researcherin Onyeka Igwe zu ihrem Buch „June Givanni: The Making of a Pan-African Cinema Archive”.

Archivierung, Widerstand und Freiheit sind die Themen dieser Publikation. Was bedeuten Erinnerung und Widerstand im Kontext deiner eigenen künstlerischen Praxis?

In meiner eigenen Arbeit sind sie untrennbar mit meinen Vorstellungen von der Gegenwart verbunden, und damit, wie man sich politisch in der Welt, in der wir leben, engagieren kann. Ich beschäftige mich mit Geschichte und meinen eigenen Erinnerungen, aber auch mit Erinnerungen an Politik und Widerstand anderer Menschen. So habe ich vor einigen Jahren eine Filmreihe gemacht – ich habe über den Aufstand der Frauen von Aba1, also über antikolonialen Widerstand nachgedacht, und ich wollte verstehen, welche Erinnerungen die Menschen an diesen Moment hatten. Ich versuche, meine Gedanken in der Gegenwart zu inspirieren. Das ist in meiner Praxis miteinander verknüpft.

Was meine eigenen persönlichen kulturellen Erinnerungen angeht, so hat mein Vater mich und meine Geschwister alle Filme im Kino sehen lassen, die wir sehen wollten, und jede Menge DVDs von Blockbustern ausgeliehen. Wir wurden dadurch sehr experimentierfreudig. Wir haben alles Mögliche gesehen. Ich erinnere mich, dass ich mit vielen verschiedenen Arten von Independent-Filmen in Berührung kam, und das hat meinen Horizont und mein Interesse am Film wirklich erweitert. Ich würde nicht sagen, dass ich damals schon an eine Karriere im Film gedacht habe, aber es hat eine tiefe Wertschätzung für den Film geweckt, Film wurde in meiner Vorstellung zu etwas, das voller Möglichkeiten ist. Ich glaube, diese Erfahrung hat mir eine bestimmte Perspektive auf Filme eröffnet.

Dein Buch „June Givanni: The Making of a Pan-African Cinema Archive“ ist dieses Jahr (Mai 2025) erschienen. June Givanni ist eine Koryphäe in der Welt des afrikanischen Diaspora-Films, insbesondere im Bereich Kuratieren und Archivieren. Was waren Höhepunkte deiner Erfahrungen mit dem Archiv und der Zeit mit June?

Das Highlight war die Gelegenheit, mit so vielen verschiedenen Menschen zu sprechen. June ist die Vermittlerin des Archivs, aber aus ihr entspringt ein ganzes Netzwerk und eine Gemeinschaft von Filmemachern. So konnte ich mit Filmemachern und Menschen sprechen, die mit jedem der vier Festivals zu tun hatten, die June kuratiert hat – Third Eye: London Third World Cinema Festival, The Pan-African Film and Television Festival of Ouagadougou (FESPACO), Images Caraïbes und Celebration of Black Cinema.

Das hat mein Wissen und Verständnis über die Filme dieser Zeit wirklich erweitert und vertieft und vielleicht auch meine eigene Arbeit beeinflusst. Es gab offensichtlich viele Menschen und sogar Werke, auf die ich aufgrund der Art und Weise, wie diese Art von Arbeit dokumentiert oder nicht dokumentiert wurde, niemals gestoßen wäre.

Ich wuchs in Großbritannien auf und hatte das Gefühl, so nah und doch so fern zu sein, obwohl diese Informationen direkt vor meiner Nase lagen. In vielerlei Hinsicht war es ein bisschen wie ein Puzzle, das ich zusammensetzen musste. Ich glaube, durch das Schreiben des Buches konnte ich das Puzzle der politischen und kulturellen Geschichte Londons zusammensetzen. Ich glaube nicht, dass ich das geschafft hätte, wenn ich keinen Zugang zu den Archiven gehabt hätte, oder ich hätte länger gebraucht.

Das war also das Highlight: die Geschichten der Mitwirkenden zu hören, sie aus verschiedenen Perspektiven zu verstehen und ein Verständnis für den panafrikanischen Film zu entwickeln, das über das hinausging, was ich zu Beginn des Buches hatte.

Das Buch über June Givanni ist Teil der Reihe Radical Black Woman2 Series, die Publikationen über Claudia Jones und Amy Ashwood Garvey umfasst. Was an Junes kreativem Schaffen war besonders radikal für dich?

Ich denke, die Art und Weise, wie das Archiv entstanden ist, ist nicht traditionell. Es entspricht nicht den Normen eines Archivs, wie man es normalerweise in einer Bibliothek oder einer institutionellen Einrichtung vorfindet. Es ist in vielerlei Hinsicht wie ein Gegenarchiv oder nutzt feministische Archivierungspraktiken, bei denen es um marginalisiertes Wissen geht. Ich bin fest davon überzeugt, dass das Archiv durch persönliche Geschichten und Netzwerke zu einem Ganzen wird und Bedeutung erhält. So wurden auch meine Erfahrungen bereichert durch Gespräche mit June, durch ihre Geschichten, ihre Abschweifungen, wenn sie etwas aus einem Regal holte und mir einen Film zeigte. Oder wenn jemand ins Archiv kam, von dem oder der ich vage gehört hatte und mich unterhielt – das ist für mich ein Gegenarchiv. Es ist also eher ein Erfahrungsarchiv als etwas, das sich mit Aufzeichnungen, Katalogen und Material befasst. Ich denke, das ist seine Stärke. Ich finde Junes Ansatz, diese Idee einer internationalen Solidarität, die Film, Gemeinschaften und eine Art Bewegung verbindet, indem sie die Idee der Befreiung durch Politik nutzt, radikal.

![]()

Onyeka Igwe bei einem Talk über June Givanni. Foto Lewis Patrick

Gehen wir zu FESPACO3, dem panafrikanischen Film- und Fernsehfestival in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. Deine Dokumentation von Junes Reflexionen über die Anfänge des FESPACO unter der Regierung von Präsident Thomas Sankara ist besonders reichhaltig. Was kann die jüngere Generation afrikanischer Filmemacher deiner Meinung nach aus dem Erbe des FESPACO mitnehmen?

Ich hatte dieses Jahr (2025) zum ersten Mal die Gelegenheit, dorthin zu reisen, und es war sehr interessant, nachdem ich so viel darüber gehört hatte und auch die Reflexionen der Menschen darüber, wie es sich verändert hat, dass es nicht mehr ganz dasselbe ist, dass es nicht mehr dieselbe Energie hat. Was junge Menschen meiner Meinung nach mitnehmen können, ist, was es für die Filmkultur bedeutet, von politischen Ideen durchdrungen zu sein. Das ist auch meine Erfahrung mit dem FESPACO selbst.

Es ist ein staatliches Filmfestival, das versucht, durch seine Rituale, den Ablauf und die Auswahl der Filme Ideen zu vermitteln. Es fördert gewissermaßen die Idee des Panafrikanismus durch die Filmkultur. Diese Art von Beziehung kenne ich hier in Großbritannien oder allgemein im Westen nicht.

Bei FESPACO ging es darum, dass afrikanische Filmemacher sagten: Wir haben afrikanische Filme, und sie sehen so aus, sie verhalten sich so, sie halten sich an diese Traditionen. Und ich denke, das hat eine wirklich reiche Filmgeschichte hervorgebracht. Was bedeutet es also, unter diesem Banner zu arbeiten, anstatt individualistisch zu sein?

Wie haben die Recherchen und das Schreiben deine eigene kreative Entwicklung und deine radikalen Neigungen beeinflusst?

Ich glaube, es hat mich definitiv dazu gebracht, meine Einstellung und mein Denken in Bezug auf Panafrikanismus zu überdenken. Ich hatte eine ziemlich ablehnende Haltung dazu, wie es sich entwickelt hat, und habe gar nicht gemerkt, dass der Einfluss dieser panafrikanischen Ideen in meine Arbeit und meine Interessen eingeflossen ist. Ich habe mich schon immer für Kollektivismus interessiert, aber das hat nur noch verstärkt, wie wichtig mir das ist und wie ich das in meiner Arbeit umsetzen möchte.

Ich möchte, dass meine Filme einen Bezug zum Politischen haben. Ich glaube, ich habe bisher um das Thema herumgetanzt und wusste nicht genau, wie ich es benennen und mich damit auseinandersetzen sollte, aber jetzt fühlt es sich viel dringlicher an, und ich bin mutiger, mich nach dem Schreiben des Buches expliziter dazu zu äußern.

Hat die Zeit, die du mit June im Archiv verbracht hast, deine eigene Wahrnehmung von der Entwicklung eines Archivs beeinflusst? Wie siehst du die Bedeutung von Archiven im Kontext deiner filmischen Arbeit und deiner künstlerischen Praxis jetzt?

Weißt du was? Ich bin eine furchtbare Archivarin meiner eigenen Sachen! Ich bin keine, die wirklich über Vermächtnisse nachdenkt. Ich habe nie wirklich darüber nachgedacht, wie ich die Recherchen, die in meine Arbeiten einfließen, aufbewahren soll. Zu sehen, was andere gemacht haben, hilft in der Gegenwart und macht dich mutiger, weil du siehst, dass du nicht allein bist. Deshalb denke ich, dass ich mich wohl etwas mehr mit dem Archivieren beschäftigen sollte. Das ist mir jetzt etwas bewusster. Ich glaube, es braucht einfach ein bisschen Zeit und Engagement, denn wenn ich ein Projekt abgeschlossen habe, bin ich oft einfach erschöpft. Es ist eine große Herausforderung, sich in einen kreativen Modus zu versetzen und dann auch noch über den Archivierungsprozess nachdenken zu müssen.

Im September 2025 hast du eine Ausstellung in der Tate Britain ...

Die Ausstellung konzentriert sich auf die Geschichte der ersten Universität Nigerias, der University of Ibadan, die meine Mutter in den 1970er Jahren besucht hat und die eine Art Ort für verschiedene Projektionen ist. Es war eine koloniale Universität, die als Vorbild des Tropical Modernism galt. An dieser Universität studierten Größen der nigerianischen Literatur wie Chinua Achebe, Wole Soyinka und Christopher Okigbo. Sie war von einer politischen Geschichte geprägt, bestimmte marxistische Akademiker wurden von dort verwiesen. Das interessiert mich, weil es meine ersten Erinnerungen an Bildung und das Potenzial von Bildung geprägt hat. Ich erforsche also die Vielfalt und Vorstellungskraft anhand der Geschichte dieses besonderen Ortes. Es gibt Videos, analoge Filmtechniken und auch skulpturale Elemente. Mit dieser Ausstellung möchte ich etwas ambitionierter sein und mit verschiedenen Medien experimentieren.

1 Ein antikolonialer Protest, der 1929 in den südöstlichen Provinzen Nigerias stattfand.

2 Der Schwerpunkt der Reihe „Radical Black Women” liegt auf den besonderen Beiträgen schwarzer Frauen zu sozialen Gerechtigkeitsbewegungen in Großbritannien.

3 FESPACO, das Panafrikanische Film- und Fernsehfestival von Ouagadougou, ist ein alle zwei Jahre stattfindendes Filmfestival in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. Es ist die größte regelmäßige Kulturveranstaltung auf dem afrikanischen Kontinent, bei der afrikanische Filme gezeigt und die Verbreitung und Entwicklung des afrikanischen Kinos gefördert werden.

Onyeka Igwe ist eine in London geborene und lebende Moving Image Künstlerin und Researcherin. Ihre Arbeit befasst sich mit der Frage: Wie leben wir zusammen? Dabei geht es ihr nicht darum, eine starre Antwort zu geben, sondern die Nuancen der Gegenseitigkeit und Koexistenz in unserer zutiefst individualisierten Welt herauszuarbeiten. Onyekas Praxis betrachtet sensorische, räumliche und gegenhegemoniale Wege des Wissens als zentral für diese Aufgabe. Sie interessiert sich für die prosaischen und alltäglichen Aspekte einer Black Livingness. Für sie sind der Körper, Archive und mündliche wie schriftliche Erzählungen Mittel der Untersuchung, die es ermöglichen, übersehene Geschichten sichtbar zu machen. Ihre Arbeiten bestehen aus dem Entwirren von Strängen und Fäden, verankert durch einen rhythmischen Schnittstil und eine genaue Aufmerksamkeit für die Dissonanzen, Reflexionen und Verstärkungen, die zwischen Bild und Ton entstehen. www.onyekaigwe.com

Dieser Text erscheint in der Publikation:

Cinéma Africain – Archiving, Resistance and Freedom

Edited by Nadia Denton and Sandra Krampelhuber

Published by JAAPO – Für Partizipation von Women* of Color, 2025

CINÉMA AFRICAIN!

Das internationale Filmfestival findet vom 5.–8. November 2025 zum zweiten Mal im Moviemento Kino und an weiteren Veranstaltungsorten in Linz statt. Mit internationalen Gästen präsentiert das Festival ein vielfältiges Programm und stellt die Publikation „Cinéma Africain – Archiving, Resistance and Freedom“ vor. Das Programm sowie alle Detailinformationen werden auf der Festivalhomepage veröffentlicht: www.cinema-africain.at.

English version

Archiving as a Radical Act

The Festival Cinéma Africain! will take place this year from November 5 to 8 in Linz, bringing films from Africa and the African diaspora to Linz. This year's edition of the festival will also be accompanied by a publication referencing the wide-ranging Pan-African film community. This Referentin features texts from the publication.

June Givanni. © Lewis Patrick

In October 2024, the first edition of the Cinéma Africain! festival took place in Linz. In order to continue the discussion on African and diasporic cinema, a publication was initiated that highlights the role of African cinema in terms of its narratives, the preservation of cultural memory, and the questioning of dominant perspectives. Editors Sandra Krampelhuber and Nadia Denton set out to compile a collection of texts that would go beyond academic circles, question Eurocentric perspectives, and celebrate the diverse traditions of African storytelling. The publication “Cinéma Africain - Archiving, Resistance and Freedom” will now be presented as part of this year's Cinéma Africain! festival. This Referentin features two texts from the publication that focus on the richness of African and diasporic storytelling in film.

In this piece UK curator Nadia Denton interviews moving image artist and researcher Onyeka Igwe about her book ‘June Givanni: The Making of a Pan-African Cinema Archive’.

Archiving, Resistance and Freedom are the themes for this publication. What does memory and resistance mean to you in the context of your own artistic practice?

In my own work, they're completely tied to ideas I have about the present and how to politically engage with the world that we live in. I look to history. I engage with my own memories, but also other people's memories of politics and resistance. So, there's a film series that I did a few years ago - I was about thinking about the Aba Women’s Riot1, thinking about anti-colonial resistance and I was interested in understanding what people's memories of this moment, were, and I'm always trying to do this to inspire my thoughts in the present. So, they're really interlinked, I think, for my practice.

In terms of my own, personal cultural memories that have influenced me in working in film, my dad used to entertain [me and my siblings] by letting us, like watch any films we wanted in the cinema and borrow loads of DVDs from Blockbusters. Me and my brother and sister just became very experimental in our choices. We watched everything and anything. I just remember being exposed to lots of different types of independent cinema and in that moment, it really like broadened my horizons and my interest in film. I wouldn't say I was thinking about a career in film, but it really established a deep kind of appreciation of film as full of possibility in my imagination. I think this experience opened a certain perspective of seeing film.

Your book June Givanni: The Making of a Pan-African Cinema Archive was launched this year (May 2025). June Givanni is a luminary in the world of African Diaspora film and in particular curating and archiving. What were some of the highlights from your experience of the archive and time spent with June?

The highlight was getting the opportunity to talk to so many different people. June is the conduit of the archive, but from her springs out a whole network and community of filmmakers. So, I got to speak to filmmakers and people who were associated with each of the four festivals that June had curated - Third Eye: London Third World Cinema Festival, The Pan-African Film and Television Festival of Ouagadougou (FESPACO), Images Caraïbes, and Celebration of Black Cinema.

It really expanded and developed my own knowledge and understanding of those films of that period and also perhaps like how I would like to orient my own work. There were obviously a lot of those individuals and even their works that I would have had no prospect of coming across because of how the history of this kind of work has been documented or not documented.

As someone who grew up in the UK, I had the feeling of being so close but so far and that this information has just been under my nose. In many ways it was a little bit of piecing together. I think in writing the book, I could piece together the puzzle of a political and cultural history in London. I don't think I would have got there or maybe it would have taken me longer to get there if I didn’t have access to the archive.

So, that was the highlight, hearing these contributor’s stories, understanding from a diversity of perspectives and formulating an understanding of pan African film, that was broader than the notion I came to the book with.

The book is part of the Radical Black Woman2 Series which includes publications about Claudia Jones and Amy Ashwood Garvey. What did you observe as radical in terms of June’s own creative practice?

I think the way that the archive has come to be is not traditional. It's not the way that archives usually exist in terms of the norms of a library or an institutional archive. It is like a counter archive in many ways, or even uses, what people describe as, feminist archiving practices, which are about marginalized knowledge. I really think the archive becomes whole or becomes meaningful through personal stories and networks. My experience has been enriched from talking to June and her telling me a story, going off on a tangent, pulling something from a shelf, showing me a film. Or someone coming into the archive, that I've vaguely heard about and who I ended up having a conversation with, for me is a counter archive. So, an experiential archive rather than something that's about records, catalogues and material. I think that's its strength. I do think that June's approach, the whole idea of creating this kind of internationalist solidarity that connects film, communities and a kind of movement using this idea of liberation through politics is radical.

![]()

Onyeka Igwe in a talk about June Givanni. © Lewis Patrick

Your documentation of June’s reflections about the early days of FESPACO3 under President Thomas Sankara’s government are particularly rich. What do you think that the younger generation of African filmmakers can take away from the legacy of FESPACO?

I had the opportunity to go to the for the first time this year (2025) and it was quite interesting after hearing so much about it and also people's reflections on it and how it's changed, how it's not quite the same, how it has not got the same energy. What I think will be beneficial for young people to take away is what it means for film culture to be infused with political ideas. That's also my experience of FESPACO itself.

It's a state film festival, that is trying to communicate ideas through the festival, through its rituals, how things proceed, and what films get invited. It's kind of promoting an idea of pan Africanism through film culture. That kind of relationship is not something that I experience here in the UK or broadly in the West.

FESPACO was about African filmmakers saying, we have African film, and it looks like this, it behaves like this, it adheres to these kinds of traditions. And I think that produced a real rich film history. So, what does it mean to try and work under that kind of banner instead of individualism?

How has the research and writing of the book affected your own creative trajectory and indeed radical leanings?

I think that it has definitely made me rethink my attitude, and thinking around pan-Africanism. I had a quite dismissive idea about it, how it developed and didn’t even realize that the influence of these kind of pan- African ideas seeped into my work and what I was interested in looking at. I've always been invested in collectivism, but it's just reinforced the importance of that and how I would like my work to do that.

I want my films to have a relationship to the political. I think I've danced around it and not quite known precisely how to name it and how to engage with it, but it feels so much more urgent now and I feel, I guess braver, to be more explicit about that after writing the book.

Has the time spent in the archive with June affected your own perceptions about developing an archive? How do you now see the importance of archive in the context of your filmmaking and wider artistic practice?

You know what? I'm a terrible archivist of my own things! I'm not someone who really thinks about legacies. I've never really thought so much about how to preserve the research that goes into things. Looking to see what other people have done helps you in the present and it helps you become brave and you see that you're not alone. So, I feel like I should probably start kind of engaging with archiving a little bit more. It's a little bit more in the front of my mind now. I guess it just takes a bit of time and investment really because you know, once I'm finished the project I'm often just spent. It is a big ask, I think, to be in the mindset of creation and then also have to think about the archiving process.

You have an exhibition coming up at the Tate Britain in September 2025 ….

The exhibition focuses on the history of Nigeria's first university which was the University of Ibadan where my mum went in the 1970s and is a kind of site of several different projections. It was a colonial university, it was seen as this exemplar of Tropical Modernism. It was a university where luminaries of Nigerian literature, like Chinua Achebe, Wole Soyinka and Christopher Okigbo. It had this kind of political history around it, certain expelled Marxist academics taught there. So, I'm interested in it because it kind of forms my own first memories of like education and like what the potential of education could be. so I'm exploring multiplicity and imagination through the history of this particular space. There's video, analogue film technology and there's a sculptural element as well. I'm trying to be a bit more ambitious with this show, experimenting with different kinds of media.

1 An anti-colonial protest which took place in the south-eastern provinces of Nigeria in 1929

2 The focus of the Radical Black Women series is to spotlight the specific contributions of black women to social justice movements in Britain

3 FESPACO, the Pan-African Film and Television Festival of Ouagadougou, is a biannual film festival held in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. It's the largest regular cultural event on the African continent, showcasing African films and promoting the expansion and development of African cinema.

Onyeka Igwe is a London born & based moving image artist and researcher. Her work is aimed at the question: how do we live together? Not to provide a rigid answer as such, but to pull apart the nuances of mutuality and co-existence in our deeply individualized world. Onyeka’s practice figures sensorial, spatial and counter-hegemonic ways of knowing as central to that task. She is interested in the prosaic and everyday aspects of black livingness. For her, the body, archives and narratives both oral and textual act as a mode of enquiry that makes possible the exposition of overlooked histories. The work comprises untying strands and threads, anchored by a rhythmic editing style, as well as close attention to the dissonance, reflection and amplification that occurs between image and sound. www.onyekaigwe.com

Nadia Denton is a Film Curator, Public Speaker and Social Impact Producer. She specialises in Nigerian Cinema. She has worked with the BFI London Film Festival, Berlinale EFM, British Council, Doc Society, London Film School, Sundance Film Festival and Comic Relief. She is an Honorary Senior Research Fellow at the University of Exeter.

This text appears in the publication:

Cinéma Africain - Archiving, Resistance and Freedom

Edited by Nadia Denton and Sandra Krampelhuber

Published by JAAPO - Für Partizipation von Women* of Color, 2025

CINÉMA AFRICAIN!

The international film festival will take place for the second time from November 5 to 8, 2025, at the Moviemento Kino and other venues in Linz. With international guests, the festival will present a diverse program and introduce the publication “Cinéma Africain – Archiving, Resistance and Freedom.” The program and all detailed information will be published on the festival website: www.cinema-africain.at.

Redaktionell geführte Veranstaltungstipps der Referentin

(30. Januar 2026)

_small.jpg)

___small.jpg)