Disordered/Speculative Memory

Die Referentin #41

The Referentin #41 features two texts from the publication Cinéma Africain – Archiving, Resistance and Freedom that focus on the richness of African and diasporic storytelling in film. Here Simisolaoluwa Akande is writing about trauma, memory, witnessing and relationality – and about the speculative setting of her film The Archive: Queer Nigerians.

In October 2024, the first edition of the Cinéma Africain! festival took place in Linz. In order to continue the discussion on African and diasporic cinema, a publication was initiated that highlights the role of African cinema in terms of its narratives, the preservation of cultural memory, and the questioning of dominant perspectives. Editors Sandra Krampelhuber and Nadia Denton set out to compile a collection of texts that would go beyond academic circles, question Eurocentric perspectives, and celebrate the diverse traditions of African storytelling. The publication “Cinéma Africain—Archiving, Resistance and Freedom” will now be presented as part of this year’s Cinéma Africain! festival. It will take place from November 5 to 8 in Linz.

.jpg)

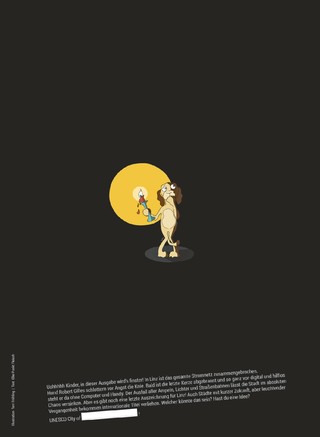

Simisolaoluwa Akande’s The Archive: Queer Nigerians. Filmstill The Archive: Queer Nigerians

The erasure of queer Nigerian ancestry allows the phrase “queerness is un-African” to persist unchallenged. This erasure splits the national self, casting queerness as “other”—a foreign imposition, that cannot be integrated into the national “I”. Both the tool and consequences of this forgetting is violence: the criminalisation of homosexual intercourse between men with a penalty of 14 years, the stoning of gay men under Sharia law, and the kidnapping and ransoming of queer bodies.

How then might we, the impossible queer Africans, claim existence and claim a right to home.

I suggest that we may attempt to “remember”.

I. Trauma and Memory

Memory is a key site of the colonial project, which determines not only what can be remembered in contemporary life, but how. The colonial project does not merely ask that we forget; it desecrates sacred artefacts of our past and rewrites our past as a traumatic memory that must necessarily be repressed. According to trauma-informed psychology, repressing traumatic memory creates unconscious conflict. Events are not recalled in coherent time and space but return as psychosomatic symptoms: fragments, flashbacks, dissociative reactions.

I am well acquainted with this kind of remembering. After almost a year of convulsing in lecture halls, collapsing in cafés, and slurring “please” and “thank you” in the back of ambulances, a Neurologist finally gave it a name: Dissociative Seizures. He told me I was remembering memories so distressing they triggered seizures. “It’s rooted in PTSD,” he said, “Common for people who have experienced war or sexual assault.”. What business do I have with such a condition? I hold no memory of war or sexual assault, no image, no known story about myself that could justify such a violent reaction.

How does one tell impossible stories, those that surpass the boundaries of the speak-able and knowable? Stories about myself that “I” was not present for? In my case my body would act it out. Each tremor leaked vile secrets of what she has survived. She tells me she has been compromised, invaded, turned inside out. That a world of mine did end, and only she was there to bear witness.

For traumatised people and groups the gap between somatic memory and cerebral memory creates an ontological schism: where subjectivity and temporality no longer cohere. My subject position, “I”, was forced to expand, to contain “we,” because my body has lived a life beyond me. She holds stories, secrets, and even joys that I cannot cognitively trace. I am no longer a singular self but a plural one; fractured across dimensions of time and experience. Over time, I have learned to transform what seemed like a disability into a generative space, where remembering is not a process of reifying a stable and coherent self-narrative but a confrontation with the multiple dimensions of self that are continually being negotiated.

By proposing “remembering” as a post/ anti-colonial strategy against queer erasure, suppression, and death in Nigeria, I invite us to take seriously our disordered memories as traumatised peoples. To regard our psychosomatic symptoms; our flashbacks, and dissociated reactions as openings into othered histories that was not allowed—wether due to colonial violence or cultural silence—to be fully actualised.

This kind of memory work requires the imaginative labour of Saidiya Hartman’s speculative fabulation, which uses storytelling and speculation to awaken alternate histories—not to recover what was lost, but to make space for what might yet be.

It is this pedagogy of remembering that I attempt to practice through my film The Archive: Queer Nigerians. This essay explores how I put these ideas into practice as an experimental filmmaker who centres memory, witnessing, and speculative imagination as tools of both personal and cultural resistance.

II. On Witnessing and Relationality

As a participant in the Oral Tradition, Nigeria has always spoken herself into existence through folklore, proverbs, poetry, riddles, and drum language.

To narrate history through spoken word is to let it pass through a body. It implicates the speaker. It demands presence, witness, and relational continuity. In this mode, history is not an external, objective record; it is lived, embodied, and co-created.

Out of darkness, a voice calls out: “Alo o”, awaiting the audience’s response. This call and response is a hallmark of Yoruba storytelling tradition. It creates reciprocity between teller and listener (or in this case, film and audience), implicating both as co-conspirators. In The Archive: Queer Nigerians, this technique becomes a cinematic device that transforms spectators into witnesses.

Where spectators remain safe behind the fourth wall, witnesses are summoned to cross it. To bear witness is to enter into a contract of presence; to be close enough to feel the weight of another’s words and to be marked by them. In this space, the boundaries between subject and object, viewer and viewed dissolve. Subjectivities blur and overflow, spilling into each other. The “I/self” expands into “us/we.” Memory, becomes relational, intersubjective, and collective.

Mainstream discourse often demands “more representation”. However, parading Black bodies on screen or excavating trauma for spectacle does not fulfil the deeper desire to be witnessed. Witnesses over audiences; this is what we long for. To witness is to have a stake in the story, and ultimately to care.

But what of being witnessed?

To be witnessed is not merely to be seen or even believed. What is at stake here is being itself—consciousness. Western philosophy tells us, “I think, therefore I am.” (Descartes), the African philosophy of Ubuntu, offers a different proposition: “I am because you are.” In this worldview, consciousness is not self-contained but emerges through relation. Being is defined through proximity to the other. Thus, I may only name what has happened to me—I may only fully be—through being seen, heard, and held by another.

In The Archive: Queer Nigerians, I invited Over 30 participants into an autoethnographic process. For over three months, they created personal audio diaries. I offered no prompts, just a request: record the sounds that make up your life. The rhythm of your commute. The silence of your bedroom. Laughter shared with loved ones. This opened up a meditative space.

Gradually, they offered more: singing half-remembered songs and whispering secrets. Unfolding personal stories about their longing for home and about the shame they carry. They addressed me by name, Simi, using it as a surrogate for the mother/father/sister/ brother they wished they could speak so transparently to. Somewhere between the anonymity of voice and the intimacy of my listening, they found the courage to say things they had never said aloud.

I was taken aback by the position they placed me in, afraid of the weight of what they were entrusting me with. This experience radically transformed my understanding of my role as a filmmaker. It is not to only tell stories but to learn to listen.

Months later, I bumped into one of the participants; the shy pastor’s son. I barely recognized him as he boldly took the streets of London, visibly and unapologetically queer. He told me, “The project changed everything for me.” His audio didn’t even make it into the final cut. But it wasn’t being “represented” that made him feel seen, it was being listened to. It was being witnessed.

People, when given the tools, space, and safety to express themselves are incredibly skilled at telling. My job as director was to guide, to make the occasional “mmm” and “yeah”, not as to decide what is true or false, but to remind them: I am here. I am listening.

.jpg)

Filmstill The Archive: Queer Nigerians

III. Speculation As Resistance

The Yoruba word Ìtàn translates not simply to “history,” but to something far more expansive: narrativity, encompassing mythology, folklore, cosmology, and ancestral memory as serious epistemologies. These are not mere stories, but knowledge systems, birthed through the divinatory practices of Ifá. Thus, for the Yoruba people history is contingent on creative processes. This epistemological openness resonates with Saidiya Hartman’s theory of speculative fabulation, which seeks to “mime the figurative dimensions of history”, using imaginative narrative to conjure lives that archive-based history refuses.

By naming the film “The Archive” I deliberately invoke the aura of empiricism and authority that such a document carries, to expose, exploit and subvert the cultural stature of “the archive” itself. I aim to disturb its position at the top of the hierarchy of discourse, to denature its facade as a neutral repository, and to reveal it as a site of power, omission, and imaginative potential.

The film opens with a queer retelling of the Yoruba creation “myth”. In contemporary Nigeria, where Christianity and Islam dominate the religious landscape, the Yoruba creation myth—telling of how Obatala, Orunmila, and Olorun created the human realm—is both, a contested and co-opted history. In the traditional Ifá literary corpus, Olorun (the supreme being) possessed no gender. Yet 19th century Christian missionaries translated the Bible into Yoruba with Olorun as “God” and Eshu as “the devil.” In doing so, they forcibly reframed Yoruba deities through a Christian lens, demonising the divine. Our gods, quite literally, were turned into devils.

By conjuring our deities, I attempt an act of speculative argumentation. I ask: What if the absence of gender pronouns in the Yoruba language suggests an alternate metaphysical order? What if our gods—tricksters, shape-shifters, liminal force—signal a lineage of ontological fluidity? These questions are not an imposition of queerness onto the Yoruba pantheon, but excavations of queerness already present. Here, queerness is not just gender or sexual variance but a deeper ontological instability—a queerness of form, of logic, of being: sensuous, non-cohesive, over-spilling.

The questions posed by the folklore sequences exploit what Hartman calls “the capacities of the subjunctive,” pulling us into a conditional temporality —a time of what could have been. To dwell in this speculative space, we must hold a dual attention: to the positive objects of history (that which is named and known), and to the absences and silences (that which has been suppressed). In this light, the film does not aim to recover a fixed past, but to awaken an archive of possibility, making space for histories felt, intuited, or imagined into being.

As the film unfolds, it resists the closure of linear time. The Orishas do not appear as relics, but as hauntings, emerging from a liminal space into the present: into the streets of Peckham, in the aisles of corner shops, and slipping between housing estates. They refuse erasure by inhabiting and troubling the now. I do not aim to illustrate them, but to activate them as living provocations.

This speculative mode also shapes how the film holds its participants. For many queer Nigerians, the present is unbearable: shaped by political violence, displacement, or exile. In such a context, the subjunctive—what if, could be, might have been—becomes a site of safety and possibility.

Each participant is filmed in a similarly liminal space. We recognise bedrooms, but they are awash in otherworldly tones. Bodies are made unfamiliar through shadow, turned faces, or silhouettes that resist grasp. In this slippery visual/temporal space, participants are able to speak what might otherwise be unspeakable: they talk to their mothers about their girlfriends and describe moments of gender euphoria. In the “real” world, many are estranged, but within this conditional temporality, they speak themselves into existence.

Through the intimate practices of listening, storytelling, and speculation, The Archive: Queer Nigerians emerges not merely as a film but as a methodology. One that reclaims the right to speak, to be heard, and to exist beyond the constraints of colonial amnesia and nationalist violence. This is not a return, but a re-membering: a weaving together of fractured selves, silenced voices, and timelines ruptured by trauma. It is at once personal and collective resistance.

My seizures, the participants’ whispers, the Orishas’ return, all converge in a refusal to forget. In place of the archive’s cold authority, we offer an embodied chorus: a living, breathing counter-memory.

By reclaiming memory as both embodied rupture and speculative repair, this essay has challenged the frameworks that render queer African life illegible.

Bibliography

Akande, Simisolaoluwa (2023). “The Archive: Queer Nigerians”, documentary film, United Kingdom, 25 min.

Hartman, Saidiya (2008). “Venus in Two Acts”, Small Axe, vol. 12 no. 2, Project MUSE, pp. 1—14.

This text appears in the publication:

Cinéma Africain—Archiving, Resistance and Freedom

Edited by Nadia Denton and Sandra Krampelhuber

Published by JAAPO—Für Partizipation von Women* of Color, 2025

CINÉMA AFRICAIN!

The international film festival will take place for the second time from November 5 to 8, 2025, at the Moviemento Kino and other venues in Linz. With international guests, the festival will present a diverse program and introduce the publication “Cinéma Africain—Archiving, Resistance and Freedom.” The program and all detailed information will be published on the festival website: www.cinema-africain.at.

Redaktionell geführte Veranstaltungstipps der Referentin

(19. Januar 2026)

_small.jpg)

___small.jpg)